Temporary Pacemaker After TAVI May Preclude Long-term Pacing

(UPDATED) The strategy allows for a 1-month “buffer period” for ascertaining whether the issues are reversible or persistent.

PARIS, France—In patients who develop conduction abnormalities in conjunction with TAVI, attaching a permanent pacemaker (PPM) outside the body for 1 month may be a temporary solution that enables them to avoid having a PPM implanted down the road.

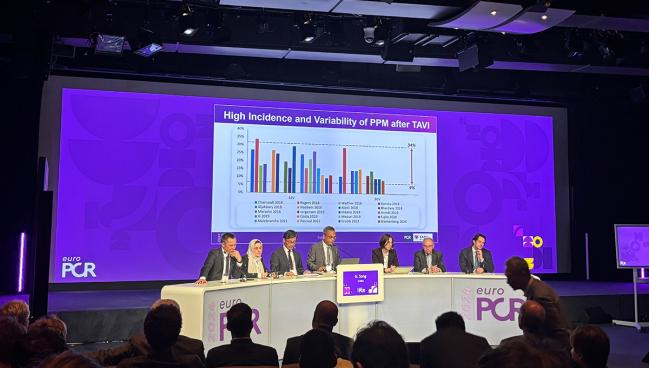

Presenting the data here at EuroPCR 2024, senior investigator Guangyuan Song, MD (Beijing AnZhen Hospital, China), pointed out that the incidence of post-TAVI PPM is high and variable, ranging from around 9% to 34% in studies conducted within the last 5 years. Yet some prior reports have suggested that pacemaker dependence after TAVI can resolve with time.

So, Song said, they decided to try a different approach: a temporary PPM that would act as a bridge for patients who require pacing in the early days after TAVI.

For the procedure, “we put a permanent lead inside the right ventricle and then we connected it to the permanent pacemaker” like usual, he explained. But instead of implanting the device, “we just [put] the permanent pacemaker on the skin.” The pacemaker is secured by sutures on the skin next to the lead implantation site using adhesive dressing.

After doing an early feasibility study of 21 patients, the research team embarked on the current project. The resulting paper, with Sanshuai Chang, MD and Zhengming Jiang, MD, PhD (Beijing AnZhen Hospital), as lead authors, was published in eClinical Medicine to coincide with EuroPCR.

“Using [temporary] PPM as a 1-month bridge after TAVR allows for a valuable buffer period to distinguish whether conduction disturbances are reversible or persistent,” Song concluded. “This could reduce unnecessary permanent pacemaker implantations, lower costs, and improve patients’ quality of life and clinical outcomes.”

Commenting on the findings for TCTMD, Amit Vora, MD, MPH (Yale School of Medicine, New Haven, CT), said: "I think this is a really interesting study and demonstrates that in select patients, the risk of needing a permanent pacemaker is variable and dependent on a number of factors."

In current practice, he continued in an email, "we often are aggressive about sending patients home with a PPM because of the risk of high-grade AV block once discharged. But even in our practice, we intuitively recognize that there are some patients that likely would recover their rhythm with a little bit of time—these are patients for whom we have targeted shallow implant, may not have preexisting conduction system disease, etc."

Most Were Free From PPM Indications at 1 Month

For their prospective, multicenter study, Song et al looked at 688 who underwent TAVI at 13 tertiary centers across China between March 2022 and September 2023. Ultimately, they enrolled 71 patients who were eligible for a temporary PPM.

All were treated via femoral access, and most received self-expandable valves. The study cohort consisted of patients with persistent complete heart block, high-degree atrioventricular block (AVB), or first-degree AVB plus new-onset left onset bundle branch block (LBBB) that occurred during TAVI or within 1 month of the procedure. None had a prior indication for PPM.

Seventy of the patients who got temporary PPM—60 with high-degree AVB or complete heart block and 10 with first-degree AVB plus LBBB—completed 1-month follow-up that included pacemaker interrogation, weekly ECG readings, and 24-hour Holter monitoring at the 1-month mark. Mean age at the time of enrollment was 74.3 years, and 41.4% were women.

Among them, 53 (76%) were free from any PPM indications at 1 month and had their temporary device removed: 13 had recovered within 48 hours, 18 by 1 week, 10 by 2 weeks, eight by 3 weeks, and four by 1 month. The remaining 14% stayed pacing dependent and were implanted with a PPM; all originally had complete heart block as the reason for receiving a temporary device. There were no recurrences of high-degree AVB within 6-month follow-up.

Using [temporary] PPM as a 1-month bridge after TAVR allows for a valuable buffer period to distinguish whether conduction disturbances are reversible or persistent. Guangyuan Song

The procedure to set up the temporary PPM took 28.6 minutes on average, with a median radiation dose of 37.8 mGy. Patients were discharged at a median of 3 days later, at which time the conduction disturbance was still present for 71.4%. Temporary pacing was used for a mean of 36 days. No adverse events occurred during the procedures to initiate temporary PPM, though by 6-month follow-up two related events occurred: a lead-related pericardial effusion and a lead dislodgement.

At baseline, there had been a higher proportion of patients with first-degree AVB in the PPM group compared with the PPM-free group (29.4% vs 9.4%; P = 0.041). Mean PR interval also was longer in the PPM versus PPM-free group (187.4 vs 169.3 ms; P = 0.03). The PPM group also had larger mean implantation depth (7.5 vs 5.7 mm; P = 0.22) and larger mean differences between membranous septum length and implantation depth (ΔMSID; 4.7 vs 2.9 mm; P = 0.040), with a greater proportion of patients having ΔMSID ≥ 3 mm (85.7% vs 43.2%; P = 0.007).

On multivariate analysis, baseline PR interval and ΔMSID ≥ 3 mm each predicted patients who would be more likely to receive PPM, while delayed occurrence of postprocedural conduction disturbance predicted patients who would be less likely to receive PPM.

“Using temporary PPM as a 1-month bridge allows for a buffer period to distinguish whether conduction disturbances are reversible or persistent, resulting in a significant reduction in the PPM implantation rate after TAVR when compared with the current strategy,” the researchers conclude.

Their results are promising, the researchers say in their paper, which is important as options for addressing post-TAVI PPM are limited at the moment.

“Prolonged ECG monitoring and temporary pacing after TAVR can help reduce PPM implantation. However, patients are increasingly being discharged within 24–48 h after TAVR, and some experts have even advocated same-day discharge in carefully selected patients,” they write. “Currently, the temporary pacing methods used during the perioperative period of TAVR are not suitable for discharged patients and are associated with a higher risk of infection, venous thrombosis, prolonged hospitalization, and delayed rehabilitation; patients should be bedridden until the pacing lead is removed to avoid dislodgement.”

Thus, strategies that protect pacing while improving mobility, shortening hospital stays, and reducing the need for permanent solutions are needed, Song and colleagues say, adding that this is especially important as TAVI moves towards younger, lower-risk patients for whom complications could affect long-term prognosis.

Vora agreed: "For many of these patients, if we had a solution that was durable in the short term but allowed patients to be discharged home, we could avoid a permanent pacemaker. This may be less of an issue for someone in their mid- to late-80s, but for someone in their 60s who potentially would have a decade or more of PPM, avoiding the need for an unnecessary device could be quite important."

Song said they are now in the planning stages for a new trial, to be called RECOVER, which will enroll patients who develop high-degree AVB after TAVI, randomizing them to receive temporary PPM either as a 1-month bridge, or for 24-48 hours.

Kentaro Hayashida, MD, PhD (Keio University School of Medicine), who moderated the late-breaking session, praised the study for addressing a question so pertinent to practice. With the temporary-pacing strategy, “I think it’s quite interesting: sometimes the patient doesn’t require a permanent pacemaker,” he said.

In the time set aside for discussion, questions came up about how exactly the pacemaker is powered and attached to the patient, among other details. Song specified, for instance, that the pulse generator is externally placed outside the body.

As for the device itself, Sondos Samargandy, MD (Prince Sultan Cardiac Center, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia), asked, “You just suture the wire? So, isn’t there risk of infection or bleeding? That’s the major concern.”

Song said that while these are valid issues to raise, in their study there were no infections—as part of protocol, standard aseptic disinfection methods and weekly wound dressing changes were done to minimize that risk.

Samargandy seemed skeptical, noting, “So how can the patients shower? They’re just going to keep that area dry for a full month?”

This is true, Song said. But as soon as the temporary PPM procedure is done, “patients can [return] to activities. . . . They can walk, they can move: whatever they want,” he added.

Philippe Généreux, MD (Morristown Medical Center, NJ), for his part, emphasized the need for studies with longer follow-up, because the PPM rate can rise after that initial 30 days. “If you look at the available data, . . . there is still a significant amount of pacemakers that happen after 1 month,” he pointed out.

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Song G. Using temporary permanent pacemaker as a one-month bridge after TAVI. Presented at: EuroPCR 2024. May 15, 2024. Paris, France.

Disclosures

- Song reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments