Cardiogenic Shock: SCAI Categories Get a Rethink as Research Rolls On

Armed with new data to make its case, SCAI will address the gray areas in shock care in an updated document.

Cardiogenic shock care continues to evolve, with revised definitions to standardize terms just weeks away and numerous trials being conducted in the US and Europe. A dedicated session at TCT 2021 gave a preview of what’s to come.

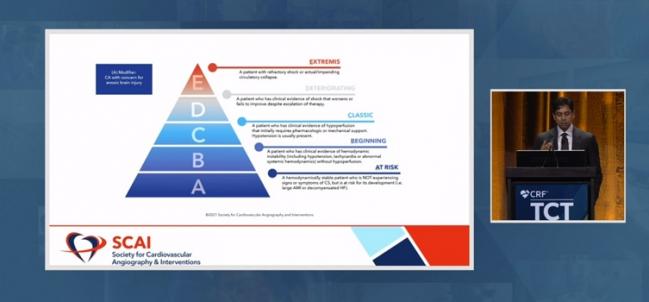

High up on the list of news is that the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) is on the cusp of releasing a consensus document that updates its 2019 classification system, the first ever developed for cardiogenic shock. Stratified into five categories, shock ranges from A (At Risk) to B (Beginning), C (Classic), D (Deteriorating), and E (Extremis).

Those designations were retained in the refreshed version, Srihari S. Naidu, MD (Westchester Medical Center, Valhalla, NY), said in his presentation. But the concepts—and the data to back them up—have been fleshed out to capture the fluidity of shock in an acute setting, the many characteristics that influence prognosis, and the tools clinicians have at their disposal in any given setting.

Having been through peer review, it’s now in the endorsement process and is expected to be published next month.

“We were really happy with this one, because the first time was a first step based on consensus opinion with really very little data,” Naidu told TCTMD. “This time obviously we had the ability to look at what happened in the interim,” in terms of both clinical experience and validation data. In doing so, they identified areas that could be clarified.

On top of improving care, such knowledge could streamline research in a notoriously difficult-to-study area, where patients can deteriorate rapidly, informed consent is hard to obtain, and an array heterogeneous conditions fall under the umbrella of “cardiogenic shock.”

Rapidly Changing Scenarios

One area of confusion, he said, was how to differentiate between B- and C-level shock, as well as between C and D, especially given that shock isn’t a static situation. Thus, the writing committee took steps to help make the distinctions more understandable, so that practitioners are consistent in how they classify shock. The table listing the various categories has been expanded to include not only what features are typically seen but also features that “may” be seen. “It helps one focus on the most common things out there in the community as people present, rather than looking at all these criteria and trying to figure out which one you have,” he explained.

The writing group also developed a three-axis model to illustrate nuances in cardiogenic shock evaluation and prognostication. Beyond shock severity, which sits at the top of the model, there are two other arrows: risk modifiers and phenotype/etiology.

“We knew that shock severity was important, but we didn’t know how to put it in context with all the other modifiers of risk” that influence mortality, said Naidu. For example, “if a patient is stage C but already lost their kidneys, that’s a different patient than [someone] who’s stage C but their kidney function’s still normal.”

Realizing this intersection is “kind of an ‘aha moment,’” he observed. “So when a patient comes in we have to modify their overall risk based on their shock severity [plus] all these other factors.” Within each shock category, there’s a spectrum, Naidu added.

Moreover, the authors looked at how their framework of physical exam, biochemical, and hemodynamic findings could be applied prior to the inpatient setting, with the “understanding that the first two are the only ones you really have in . . . the emergency room,” said Naidu, and that in the ambulance there may only be the physical exam. Earlier recognition of cardiogenic shock would enable better triage and faster treatment, he urged.

Speaking One Language

The 2019 document was endorsed by the American College of Cardiology, the American Heart Association, the Society of Critical Care Medicine, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. This time around, the collaborating organizations also include the American College of Emergency Physicians and the European Society of Cardiology Association for Acute Cardiovascular Care; the Cardiac Safety Research Consortium is involved but doesn’t endorse clinical documents.

By reaching across specialties, the 2019 categories have begun to make their mark, said Naidu.

For one thing, they’ve enabled better communication about the aims of individual studies and the populations they’re targeting. “All of a sudden all these trials are different. If you have a shock trial in B and C, that’s a very different shock trial than in D. Now people are finally thinking that way,” he said, predicting studies and registries will begin to use the categories to subgroup participants. Eventually, trials could prospectively enroll by shock severity.

Naidu said that the categories can guide decision-making, too, something already being done at his center as the SCAI shock definitions have entered the lexicon.

“I think where it’s going to be used in practice is to see over time during a hospital stay for a patient where they’re going up and down and what time frame,” he explained. This will be done by “reevaluating the biochemical and hemodynamic profiles—doing them at regular intervals yet to be defined—so that you can push people down [into a less-severe category]. As opposed to being a static definition, it’s more of a dynamic definition, where we can show ultimately if you move down in a certain time period patients do better than if they move up or stay the same.”

For someone in B, they’d check lactate level. If its high enough, the individual might move up to category C, information that could be shared with the shock team, said Naidu. “They’ll pipe in with different recommendations about what they should do to that patient, because clearly what you’re doing right now is failing. So I think that’s how it’s happening in real life.”

Studies in the Works

Other presentations in the TCT session updated attendees on the status of research on cardiogenic shock.

Mitchell Krucoff, MD (Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC), shared the latest from the Cardiac Safety Research Consortium. Starting in 2018, they’ve held periodic stakeholder meetings to address “concerns about the diffuseness of ambiguity of shock-related data for mechanical circulatory support devices,” Krucoff said, and have established five working groups: Shock Academic Research Consortium (SHARC), shock networks, resources, informed consent, and priority clinical trial(s).

In addition to developing endpoint definitions, standards for “centers of excellence,” and the like, one key project has been the American Heart Association’s Cardiogenic Shock Registry within the Get With The Guidelines program, he reported.

Holger Thiele, MD (Heart Center Leipzig, Germany), meanwhile, described an array of European trials of hemodynamic support now being conducted: the Impella left ventricular assist device (Abiomed) in DanGer plus extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) in ANCHOR, EUROSHOCK, and ECLS-SHOCK.

For the United States, William O’Neill, MD (Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, MI), summed up his experience with the National Cardiogenic Shock Initiative, which has 80 participating hospitals (60% community and 40% academic) and 406 patients enrolled nationally. Additionally, the ISO-SHOCK study of supersaturated oxygen and Impella is in the works, while the RECOVER IV trial is set to evaluate whether Impella support before PCI outperforms PCI done without Impella.

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Multiple presentations. SCAI at TCT: New Directions in Cardiogenic Shock. Presented at: TCT 2021. Orlando, FL. November 5, 2021.

Disclosures

- Naidu and Thiele report no relevant conflicts of interest.

- Krucoff reports various affiliations/financial relationships with Abbott Vascular, Abiomed, Biosensors, Boston Scientific, Cook Medical, CSI, Medtronic, OrbusNeich, and Terumo.

- O’Neill reports grant/research support from Abiomed; consulting fees/honoraria from Abiomed, Edwards, and Medtronic; and major stock shareholder/equity in Synecor.

Comments