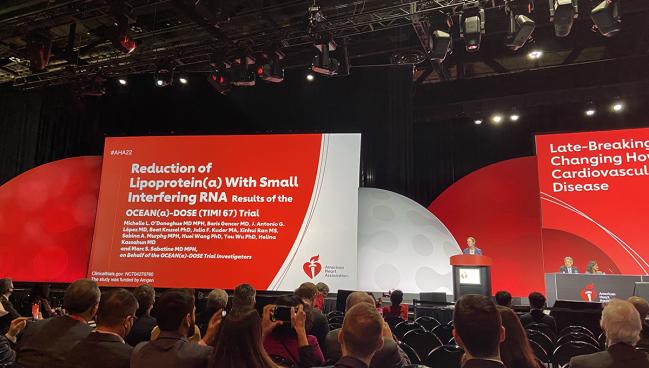

‘Dramatic’ Reductions in Lp(a) With Olpasiran: OCEAN(a)-DOSE

The siRNA therapy slashed Lp(a) concentrations by as much as 100% in this phase II study, paving the way for a larger trial.

CHICAGO, IL— (UPDATED) A small-interfering RNA (siRNA) molecule, delivered as serial injections at least 3 months apart, safely lowers lipoprotein(a) levels in patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), with some doses reducing Lp(a) concentrations by as much as 100%, a new study has shown.

The phase II study is small, but the siRNA, olpasiran (Amgen), was not associated with any adverse effects and adds more excitement to a burgeoning group of therapeutics that lower Lp(a), which researchers believe will reduce the risk of ASCVD.

Robert Rosenson, MD (Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY), one of the OCEAN(a)-DOSE researchers, called the observed reductions in Lp(a) “dramatic.”

“Currently, there are no FDA-approved therapies for lowering Lp(a), and high levels of Lp(a) are an important cause of coronary heart disease and other forms of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease,” Rosenson told TCTMD. “High levels of Lp(a) are the most common lipoprotein abnormality in men with coronary artery disease before age 50 and women before age 60. We’re often frustrated that we have many therapies that lower LDL cholesterol, but Lp(a) doesn’t change with, or may even go up with, statins and isn’t affected by ezetimibe.”

Lp(a) can decrease in some patients treated with a PCSK9 inhibitor, said Rosenson, noting there are data showing that patients who experienced a reduction in Lp(a) along with LDL cholesterol had a larger benefit from PCSK9-inhibitor treatment. The PCKS9 inhibitors can lower Lp(a) by approximately 25% to 35%, he added.

We’re often frustrated that we have many therapies that lower LDL cholesterol, but Lp(a) doesn’t change with, or may even go up with, statins and isn’t affected by ezetimibe. Robert Rosenson

Lp(a) is a very attractive target for drug manufacturers, because it’s highly genetically determined and higher levels are associated with an increased risk of ASCVD. Graded, dose-dependent associations between Lp(a) and clinical outcomes also have been seen in numerous observational studies. Roughly 20% of people with ASCVD have elevated Lp(a) levels, defined as 150 nmol/L or greater.

“We have mendelian randomization studies, genetic epidemiology studies, and classic epidemiology studies, but we don’t have a clinical [outcomes] trial yet focused on lowering Lp(a) selectively,” he said.

In the US guidelines for the treatment of high cholesterol, elevated Lp(a) is considered a risk-enhancing factor to help physicians and patients make an informed decision about LDL cholesterol-lowering treatment. In Europe, the guidelines recommend checking Lp(a) for CVD risk stratification in individuals at least once during the patient’s lifetime, although the recommendation is relatively weak.

Went Low, Stayed Low

In the OCEAN(a)-DOSE TIMI 67 trial, which was led by Michelle O’Donoghue, MD (Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA), who presented the results today at the American Heart Association 2022 Scientific Sessions, investigators randomized 281 patients (mean age 61.9 years; 32.0% women) with ASCVD and Lp(a) > 150 nmol/L to either placebo or one of four olpasiran doses: 10 mg, 75 mg, or 225 every 12 weeks, or 225 mg every 24 weeks. At baseline, the median Lp(a) concentration was 260.3 nmol/L and the median LDL cholesterol level was 67.5 mg/dL.

Patients in the trial were well treated with medical therapy, with 88% taking statins, including 61% taking high-intensity statins. More than half were taking ezetimibe, and 23% were taking a PCSK9 inhibitor.

After 36 weeks, Lp(a) levels increased 3.6% in the placebo arm. For patients treated with olpasiran 10 mg, 75 mg, and 225 mg dosed every 12 weeks, the placebo-adjusted percent reductions in Lp(a) concentrations were 70.5%, 97.4%, and 101.1%, respectively. For those taking the 225-mg dose every 24 weeks, the placebo-adjusted percent reduction from baseline was 100.5%. Among those given the 10-mg dose every 12 weeks, 66.7% achieved an Lp(a) concentration less than 125 nmol/L. At 75-mg and 225-mg doses every 12 weeks, 100% got below this threshold. At the 225-mg dose given every 24 weeks, 98.1% achieved an Lp(a) concentration less than 125 nmol/L.

There were also significant reductions in LDL cholesterol and apolipoprotein B (apoB). Across the 10 mg, 75 mg, 225 mg, and 225 mg (Q24W) doses, the placebo-adjusted percent reductions were 23.7%, 22.6%, 23.1%, and 24.8%. With apoB, the placebo-adjusted declines were 18.9%, 16.7%, 17.6%, and 18.8%, respectively.

“We were impressed not only with the fact the drug reduced Lp(a), but Lp(a) remained reduced for a very long period of time after the last subcutaneous injection,” said Rosenson. “There were some patients that had reductions in Lp(a) that lasted out to a year. It’s a very exciting approach. It’s a very select approach.”

As for safety, investigators reported similar incidence of adverse and serious adverse events with treatment and placebo. Such events leading to drug discontinuation were 2% in each of the groups, including placebo. Hyperglycemia or new-onset or worsening diabetes was also similar in the treatment arms and the placebo group, while liver- and kidney-related adverse events, thrombocytopenia, and peripheral neuropathy were all rare and similar with olpasiran and placebo.

Stephen Nicholls, MBBS, PhD (Monash University, Melbourne, Australia), the scheduled discussant following the late-breaking presentation, said “hope is in sight for patients with elevated levels of Lp(a).”

Apart from an increase in injection-site and hypersensitivity reactions, olpasiran looks to be well tolerated by patients, he said, adding that the siRNA molecule may represent another option to target the atherogenic lipoprotein.

Still, Nicholls stressed there are many unknowns about Lp(a), the first being whether or not lowering it reduces ASCVD events. Additionally, it’s not known how much Lp(a) lowering is needed to produce an effect, with genetic data suggesting that treatments may need to cut Lp(a) levels in excess of 100 mg/dL. “Many of us hope that’s not the case, because we have many patients with elevated Lp(a) levels between 70 and 100 mg/dL,” said Nicholls. “Again, we won’t know until we do these trials.”

Finally, Nicholls said one of the biggest unknowns is the long-term implication of slashing Lp(a) down to low levels.

“Why do we really have Lp(a)?” he said. “I think the jury is still out with regards to that, so what are the long-term consequences of essentially silencing it by reducing its levels by more than 90%? Will substantial Lp(a) reductions increase the rate of new-onset diabetes? There are observational analyses that show that while high Lp(a) is associated with cardiovascular risk, it’s also associated with low rates of diabetes.”

Those questions, and more, will hopefully be address in large-scale, randomized clinical trials, he said.

Phase III Study Coming Soon

In terms of those outcomes’ trials, they are coming, although olpasiran is playing catchup with the mRNA-based antisense oligonucleotide targeting the LPA gene. The drug, known as pelacarsen (Ionis Pharmaceuticals/Novartis), is already being tested in an 8,000-patients outcomes study. Known as Lp(a)HORIZON, recruitment for the trial is complete, but results aren’t expected for another 3 years, possibly sooner if the trial is stopped early.

Silence Therapeutics, a smaller, UK-based company, is also developing an siRNA known for now as SLN360. They’ve reported positive results from the APOLLO phase I study showing that SLN360 reduced Lp(a) levels by 98% from baseline when the highest dose is used.

To TCTMD, Rosenson said the reduction in Lp(a) seen with olpasiran is larger than what has been observed with pelacarsen, a drug that is dosed once per month. Based on the positive data from the OCEAN(a)-DOSE study, there are plans to launch a phase III cardiovascular outcomes study with olpasiran, which should begin in January.

“Everything is ready to go for a phase III clinical trial,” he said.

Michael O’Riordan is the Managing Editor for TCTMD. He completed his undergraduate degrees at Queen’s University in Kingston, ON, and…

Read Full BioSources

O’Donoghue ML, Gencer B, López AG, Reduction of lipoprotein(a) with small interfering RNA: results of the OCEAN(a)-DOSE TIMI 67 trial. Presented at: AHA 2022. November 6, 2022. Chicago, IL.

Disclosures

- O’Donoghue reports consulting for Amgen and Novartis. She reports grant/contracts from Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, and AstraZeneca and serving on the Data and Safety Monitoring Board for AstraZeneca and Janssen Biotech.

- Rosenson reports consulting for Arrowhead Pharmaceuticals, CRISPR Therapeutics, Eli Lilly, Lipigon, Novartis, Precision BioSciences, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Ultragenyx Pharmaceuticals, and Verve. He reports honoraria from Kowa American Corporation, stock from MediMergent LLC, and other fees from Amgen and Wolter Klewer Health.

Comments