Primary PCI After TAVI: New Real-world Insights

For patients whose STEMI occurs after TAVI, there can be delays to treatment, greater risk of PCI failure, and worse survival.

Patients who experience ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction in the context of prior TAVI face lengthier delays to treatment, greater risk of PCI failure, and worse survival compared with typical STEMI patients, new data confirm.

This doesn’t come as a surprise, Laurent Faroux, MD (Quebec Heart and Lung Institute, Laval University, Canada), and colleagues say. Beyond TAVI patients’ typically advanced age, “the poor prognosis of post-TAVR STEMI could be related to patients’ characteristics (high comorbidity burden) along with the involvement of pathophysiologic mechanisms other than atherothrombosis (impaired coronary flow, leaflet thrombosis, coronary embolism, late valve migration),” they write. There’s also the potential for delays due to an interaction between the transcatheter heart valve and the coronary ostia.

Yet knowledge about these patients had been slim, in part because they are so rare—the current study, published in the May 4, 2021, issue of the Journal of the American College of Cardiology, found a 0.3% cumulative incidence of STEMI post-TAVI.

Senior investigator Josep Rodés-Cabau, MD, PhD (Quebec Heart and Lung Institute, Laval University, and Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Spain), told TCTMD the main takeaway for clinicians is that the “tips and tricks” for successful revascularization in TAVI patients should be known by all interventional cardiologists who perform primary PCI, not just those who specialize in structural interventions.

Unlike elective or even NSTE ACS cases that tend to take place during the day, STEMIs occur around the clock. “These patients can come at midnight,” when a TAVI operator isn’t available to give input, he said, or they may present at a referral hospital without its own TAVI program. Importantly, while “plaque rupture is the main cause of infarction in these patients, there are other causes like emboli that can be there and seem to be more frequent. We should be aware of that,” Rodés-Cabau added. “We are dealing with some patients who have differential features.”

Longer PCI Times, Higher Risk of Failure

The multicenter, international study enrolled 118 patients (mean age 80 years; 50% women) who presented to one of 38 centers with STEMI post-TAVI out of a total of 42,252 TAVI recipients in the data set. Rodés-Cabau stressed the degree of collaboration this required. “I am proud of the paper, I have to say, because it was a big effort involving many, many centers in Europe and Canada,” he said.

Prior to TAVI, the STEMI patients had a mean STS-PROM score of 5.6%, seven in 10 had known CAD, and 12.7% had a previous CABG surgery. Around one-third had no significant lesions on coronary angiography, and 42.4% had multivessel disease. A sizeable proportion had undergone PCI prior to their aortic valve intervention.

Sixty percent of the STEMI patients were discharged after TAVI on dual antiplatelet therapy, 21.2% on an oral anticoagulant (with or without an antiplatelet), and 17.0% on a single antiplatelet. A small minority (1.7%) did not receive any antithrombotics.

Patients presented with STEMI at a median of 255 days after TAVI, with 34.7% occurring in the first month. They tended to be in an unstable clinical condition; nearly half (47%) had congestive signs at admission, 18% were in cardiogenic shock, and 11% were in cardiac arrest. Notably, “a nonatherothrombotic mechanism (coronary embolism, late prosthesis migration) was involved in ~15% of cases,” Faroux et al report.

Compared with 439 non-TAVI controls who underwent primary PCI, the 102 post-TAVI patients who underwent primary PCI had longer door-to-balloon, procedural, and fluoroscopy times, resulting in higher dose-area product and contrast volume. They also were more likely to see PCI failure, most often failure to cannulate the coronary ostium (n = 5) or to cross the lesion (n = 4).

Primary PCI Characteristics of STEMI Patients: With Versus Without Prior TAVI

|

|

After TAVI |

Controls |

P Value |

|

Median Door-to-Balloon Time, min |

40 |

30 |

0.003 |

|

Median Procedural Time, min |

46 |

36 |

< 0.001 |

|

Median Fluoroscopy Time, min |

18.3 |

10.1 |

< 0.001 |

|

PCI Failure |

16.5% |

3.9% |

< 0.001 |

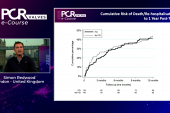

In-hospital mortality was higher for the post-TAVI primary PCI patients than for the controls (25.4% vs 20.6%), as was late mortality at a median follow-up of 7 months (42.4% vs 38.2%). On multivariable analysis, predictors of increased mortality risk included estimated glomerular filtration rate < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2 (HR 3.02; 95% CI 1.42-6.43), Killip class ≥ 2 (HR 2.74;95% CI 1.37-5.49), and PCI failure (HR 3.23; 95% CI 1.42-7.31).

“These results highlight the urgent need for a better understanding of coronary cannulation difficulties and the techniques for enhancing coronary access and improving PCI success rates and clinical outcomes in this population,” the researchers conclude.

Unique Challenges

To TCTMD, Rodés-Cabau observed that post-TAVI primary PCI is not universally complex. “Many cases can be treated very easily,” he commented. Difficulties can arise when the transcatheter valve interacts with the cutoff of the coronary ostia, which makes the procedure more challenging. That’s reflected, he noted, by the fact that post-TAVI primary PCI in this study was more likely to involve use of two or more guide catheters. There also was more-frequent use of nonselective injection with the guide catheter and use of a guide catheter extension.

One pleasant surprise to the researchers was that the TAVI patients tended to present to the hospital earlier after symptom onset than did the controls (median 130 vs 180 minutes; P = 0.015). “In the [latter] group you have a significant number of patients for which this is the first cardiac event. . . . But the ones who had a TAVR procedure, when they feel something in the chest, say, ‘Wow, something is wrong there.’ Many of them already had prior coronary disease,” such as a previous MI or angina, he explained.

Indeed, as Luis Gruberg, MD, and Puneet Gandotra, MD (both from South Shore University Hospital and the Donald and Barbara Zucker School of Medicine at Hofstra/Northwell Health, Bay Shore, NY), note in an editorial, all of the post-TAVI STEMI patients had undergone angiography at the time of their valve intervention and fully 39% were treated then by PCI.

Operators have begun to shift away from the strategy of performing PCI as a combined procedure at the time of TAVI out of concerns for future access problems; last year’s ACTIVATION trial helped cement the strategy of watchful waiting. Tackling preexisting or worsening CAD post-TAVI will be especially relevant as the field evolves, Gruberg and Gandotra note. “As a younger generation of lower-risk patients undergoes TAVR, progression of coronary disease may become a concern given the natural course of this disease.”

For now, the best timing for revascularization in nonurgent cases “remains controversial,” they say, “but in the setting of STEMI in a post-TAVR patient, primary PCI, despite all its technical difficulties and challenges, should still be the treatment of choice.”

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Faroux L, Lhermusier T, Vincent F, et al. ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction following transcatheter aortic valve replacement. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:2187-2199.

Gruberg L, Gandotra P. STEMI following TAVR: unusual but definitely not trivial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77:2200-2203.

Disclosures

- Faroux has received fellowship support from Institut Servier and the Association Régionale de Cardiologie de Champagne-Ardenne (ARCCA), as well as research grants from Biotronik, Edwards Lifesciences, and Medtronic.

- Rodés-Cabau has received institutional research grants from Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, and Boston Scientific; and holds the Research Chair “Fondation Famille Jacques Larivière” for the Development of Structural Heart Disease Interventions.

- Gruberg and Gandotra report no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments