Structural Heart Disease Imagers Call for Greater Recognition, Focused Training

The burgeoning field of structural heart imaging has grown beyond “on-the-job” training. Experts say the time has come for dedicated programs.

Given the growth seen over the last few years within the field of structural heart interventions and an increasing dependence on imaging to guide these procedures, a cadre of physicians representing the entire heart team is calling not only for systematic recognition of the burgeoning subspecialty of interventional imaging but also for appropriate resources and a training curriculum to sustain it moving forward.

“Recognition of structural heart disease interventional imaging as a subspecialty of cardiac imaging is necessary and should be accompanied by formalized training programs,” write Dee Dee Wang, MD (Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI), and colleagues in a letter to the editor published online last month in JACC: Cardiovascular Imaging. “However, the relative novelty of this subspecialty and the poorly defined training requisites and skillsets are important barriers to this goal. Furthermore, there is a significant mismatch between the amount of time needed to plan and guide complex structural heart disease procedures and current reimbursement attributed to the structural heart disease imager.”

Especially following the positive results of the COAPT trial presented last week, which showed reductions in heart failure rehospitalizations and mortality at 2 years following transcatheter mitral valve repair using the MitraClip (Abbott), enthusiasm for transcatheter mitral therapies has increased substantially, Wang told TCTMD. But “all these mitral procedures are not possible without imaging guidance,” she stressed. “They're 100% TEE, intraprocedural-imaging guided.”

A Call to Action

Wang views their letter to the editor as a call to action that “shines a light on the fact that the person doing the imaging actually needs protection, not only from a radiation safety standpoint but [having] time to actually do these procedures. . . . A lot of us who are passionate about doing interventional imaging in this field do it at a cost, because there is no productivity metric for the line of work that we do. Because of all the new clinical trials and devices, all the metrics of productivity are being assigned to [how many devices are actually implanted] but not the imaging to make that device happen.”

Right now, much of the work that structural heart imagers do cannot be accounted for in the current RVU-based system and is thus not reimbursable, she explained. For example, a single TAVR CT can take an hour of planning, Wang said. “This involves finding multiple alternative access routes (transfemoral, transcaval, transcarotid, subclavian, and versus axillary approaches), valve sizing (for different valve types), coronary evaluation, cerebral protection, and valve deployment angulation and virtual simulation. However, that work is not covered under traditional RVU metrics, so this 1 hour spent is not reflected in productivity.”

This has led many institutions to ask these physicians to account for their work through time sheets or other means, but even so, Wang stressed, “if structural heart disease imagers are judged by current traditional productivity metrics, there would not be enough time in the day for them to fulfill both the traditional cardiology productivity metrics and nontraditional job descriptions.” Something has to change, she said, specifying that a good first step would be to switch to a salary model.

Senior author João L. Cavalcante, MD (University of Pittsburgh, PA), agreed. “It is good timing for us to now bring this to the forefront [of] discussion,” he told TCTMD, adding that MitraClip implantation and other novel structural procedures cannot be done without an interventional echocardiographer. “But how can we continue to sustain this model, which was probably not very well thought through from the beginning? . . . Some centers have been creative on how to better negotiate and distribute the effort, but [currently at] the majority of centers actually, there's a lot of complaints,” he said.

At the same time, both Wang and Cavalcante say they are fielding many requests from fellows who want to follow their career paths and are looking for advice on how to do so. Thus, their letter not only “outline[s] the difficulties of how we can achieve adequacy of training and competency, but also how this model can be continued to be sustained,” Cavalcante said.

“We're still stuck in ‘noninvasive imaging,’ and we're not really focused on training an invasive imager who's actually going to be equally invested as an implanter to learn a device like the implanter to avoid complications,” Wang added.

Specifically, the authors say that structural heart imagers must be trained in the following skills:

- Preprocedural adjudication to justify intervention

- Rapid integration of clinical information with imaging findings

- Dynamically integration of multiple imaging modalities with hemodynamic interpretation

- Timely, succinct, and clear communication of imaging results during a procedure

- Knowledge of common terminology for imaging landmarks

- Postprocedural correlation of imaging findings with intraprocedural results and evaluation for potential complications

- Exposure and familiarity to a variety of structural heart disease interventions

Separating From the Pack

Wang told TCTMD that training in this field right now is mostly ad hoc and on-the-job, with not every imager realizing what they are getting themselves into. And while she admits that even structural intervention training is not consistent at this point, “at least it's recognized,” she said. Also, “you can say that somebody's a CTO operator and they're a skilled CTO operator. Well, all [interventional] cardiologists can still engage that same coronary too, but why do you not feel comfortable having [an interventional] cardiologist inflate a balloon but a CTO operator can? That's the question.”

Cavalcante also said treatment of chronic total occlusion “is a good analogy, because CTO is still coronary disease but much more complex [so] you require different tools, different strategies.” As opposed to the systematic way CTO procedural training is conducted today, however, the way interventional imaging is taught “is much more on-the-fly in programs that have a high volume that somebody can tag along,” he added.

Right now, “everybody's learning together so there's no level of expertise,” said Matthew Daniels, MB BChir, PhD (Radcliffe Department of Medicine, Oxford, England), who also supports greater acknowledgement for this field. He told TCTMD that the community is facing the “same dilemma” as it did when structural interventions split off from the coronary field. “When did they become separate? When did that split happen? How do you get the recognition for it and are you so different that you need an entirely different representative body?” he asked.

While many unanswered questions remain as to how to move forward, Wang said the goal right now is to “get recognition and legitimize our careers. We really want to be legitimate. We don't want to be labeled as a noninvasive, we don't want to be . . . having to do time sheets,” to justify the time invested.

For starters, Cavalcante said he would like to see a partnership with either industry or a professional society to develop a consistent training curriculum, reimbursement models, and competency requirements for interventional imagers. “We need to build on more of this grassroots [effort] and I think we need to create noise, because this cannot be sustained the way it is,” he said.

“It's a massive challenge, but it's the right thing to do because things have now progressed to a stage where you can teach things,” Daniels said. “People have learned the early mistakes. The devices have changed. The imager needs to be as aware of the device and its limitations as the person putting it in.”

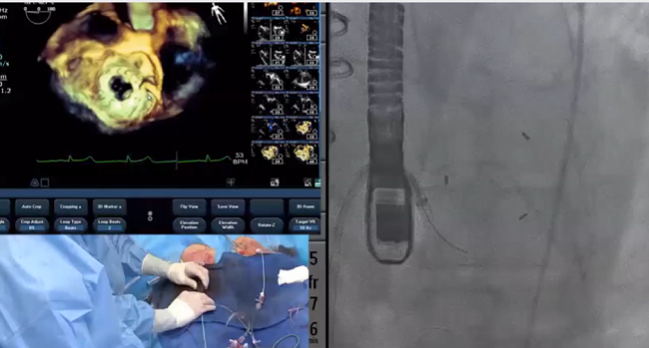

Photo Credits: Header image: Dee Dee Wang. Teaser image: adapted from Live Case: Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, MI. Presented at: TCT 2018. September 23, 2018. San Diego, CA.

Yael L. Maxwell is Senior Medical Journalist for TCTMD and Section Editor of TCTMD's Fellows Forum. She served as the inaugural…

Read Full BioSources

Wang DD, Geske J, Choi AD, et al. Navigating a career in structural heart disease interventional imaging. J Am Coll Cardiol Img. 2018;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- Wang reports serving as a consultant to Edwards Lifesciences, Boston Scientific, and Materialise.

- Cavalcante reports receiving research grant support from Medtronic and serving as a consultant for Medtronic and Mitralign.

- Daniels reports no relevant conflicts of interest.

Comments