High-risk Plaques in Nonculprit Lesions Tied to Worse Post-MI Outcomes

Observational data suggest a role for OCT in deciding which FFR-negative lesions may still cause later events.

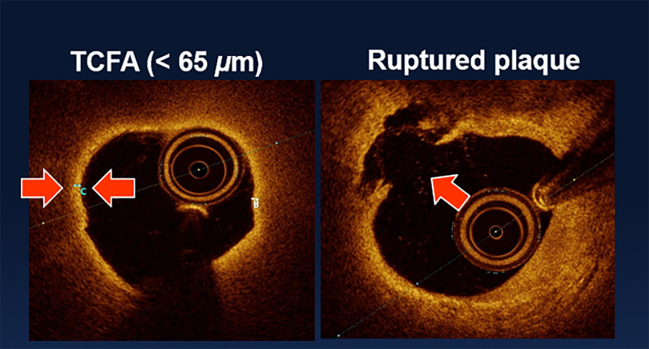

Photo Credit: Adapted from: Ambrose JA. TCT-54: The distribution of hgh-risk plaques with respect to artery stenosis in non-culprit non-ischemic native coronary lesions of diabetic patients: data from COMBINE OCT-FFR study. Presented at: TCT 2018. San Diego, CA.

High-risk plaque on optical coherence tomography (OCT) in nonculprit lesions after myocardial infarction is a harbinger of worse outcomes to come, even in patients whose fractional flow reserve (FFR) values suggest no further treatment is needed, according to results from the observational PECTUS-obs study.

By 2 years, patients with these high-risk plaques had nearly twice the risk of MACE as those without them—with the gap explained largely by repeat revascularization.

“Recurrent coronary events are frequently observed after myocardial infarction, despite advances in primary treatment, complete revascularization, and secondary prevention,” investigators note in a paper published September 13, 2023, in JAMA Cardiology.

Both FFR and angiography can help operators choose which lesions must undergo treatment in order for revascularization to be “complete.” But for MI patients, unlike those with stable CAD, FFR may not outperform angiographic guidance, they explain. “This is probably related to the fact that FFR alone reveals plaque morphology to a limited extent. Moreover, FFR might be false-negative in the acute setting of MI.”

This is where OCT may serve as a potential diagnostic tool to “unmask high-risk nonculprit lesions in MI,” Jan-Quinten Mol, MD (Radboud University Medical Center, Nijmegen, the Netherlands), and colleagues suggest.

Senior author Niels van Royen, MD, PhD (Radboud University Medical Center), explained to TCTMD that FFR and OCT aren’t in competition.

“Of course, FFR is still the cornerstone for decision-making in [the choice of] revascularization or not, but what we show here is that there is definitely something beyond physiology. So with OCT, or in general with intravascular imaging, we are able to identify those patients that have additional risk despite having a negative FFR,” said van Royen. “In the past we would simply say, ‘Okay, the FFR is negative: perfect, leave it alone and don’t worry anymore.’ Now more and more we understand that there is a cohort of patients”—around one-third of participants in the PECTUS-obs study—who “have high-risk plaques, and these high-risk plaques are associated with more adverse events in the years to come.”

Davide Capodanno, MD, PhD (University of Catania, Italy), told TCTMD that the PECTUS-obs study results speak to the overarching question of anatomy versus physiology: the information provided by intravascular imaging versus by functional assessment.

This paper, he said, joins COMBINE OCT-FFR and other trials showing “that even when you have no proof of ischemia by FFR or physiological indexes, the vulnerable plaque characteristics may really predict the future events.”

The fact that in this study the 2-year MACE rate was indeed higher for individuals with high-risk plaques suggests there may be a phenotype of patients vulnerable to future events and serves as a reminder of how atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease is a dynamic process. These plaques, said Capodanno, “are not necessarily those responsible for the events, but characterize a high-risk population where this plaque, it ruptures and it heals. . . . When you have this kind of phenotype, you are at risk for MACE.”

For both van Royen and Capodanno, the question remains: what should be done if a patient is found to have high-risk plaque?

The PECTUS-obs Study

At the recent European Society of Cardiology Congress in Amsterdam, several studies focused on how periprocedural OCT might impact PCI outcomes by improving stent implantation, with mixed results. Here, the imaging tool is being put to a different use: analysis of plaque composition.

Led by Mol, the PECTUS-obs researchers enrolled 438 MI patients in their prospective, observational study that took place at 14 centers in four countries. All underwent FFR, and thereafter OCT was performed on all FFR-negative ( > 0.80) lesions.

In total, there were 420 patients (mean age 63 years; 81% men) with analyzable OCT images for a total of 494 FFR-negative nonculprit lesions (mean 1.17 per patient). Around half had presented with STEMI and half with NSTEMI.

Fully one-third of the patients (34%) had at least one high-risk plaque, defined as a plaque that met two or more of these criteria: a lipid arc ≥ 90°, a fibrous cap thickness < 65 μm, and either plaque rupture or thrombus presence.

The primary endpoint of MACE (all-cause death, nonfatal MI, or unplanned revascularization) at 2 years was more common in patients with versus without a high-risk plaque (15.4% vs 8.3%; P = 0.02). This increased MACE risk (HR 1.93; 95% CI 1.08-3.47) was mainly driven by unplanned revascularization, which occurred in 9.8% of those had a high-risk plaque and 4.3% of those who did not.

“In a population with a high recurrent event rate despite physiology-guided complete revascularization, these results call for research on additional pharmacological or focal treatment strategies in patients harboring high-risk plaques,” Mol and colleagues conclude.

For MI patients, especially those with complex multivessel disease, the findings make the case for greater vigilance, van Royen said. “I think that we have to take better care of this subset of patients with high-risk plaques.” He added that subsequent studies can provide clarity on which treatments best address this need.

Van Royen stressed: “This is a set of patients that deserves extra attention.”

Capodanno agreed that, clinically speaking, the most important thing is figuring out what to do next, whether that’s reducing inflammation or taking steps to decrease the lipid content of the plaques. “I think the most-established therapies now are the lipid-lowering therapies, which have very little side effects, probably none,” he said, adding, “It is something that is done now, not just with the statins, but with a lot of drugs,” including the newer small-interfering RNA-based inclisiran as well as the more-established PCSK9 inhibitors. And for inflammation, there’s colchicine as well as other drugs currently in the pipeline.

“Targeting both inflammation and lipids can be something really important, because you go looking for a systemic effect rather than a localized effect,” Capodanno commented.

Another option under study is additional stenting in high-risk lesions, van Royen noted, a hypothesis tackled in the PROSPECT trials and others. As of yet, though, the best way to definitively prevent events in vessels deemed to be high risk is unknown, he added.

Caitlin E. Cox is Executive Editor of TCTMD and Associate Director, Editorial Content at the Cardiovascular Research Foundation. She produces the…

Read Full BioSources

Mol J-Q, Volleberg RHJA, Belkacemi A, et al. Fractional flow reserve–negative high-risk plaques and clinical outcomes after myocardial infarction. JAMA Cardiol. 2023;Epub ahead of print.

Disclosures

- This study was supported by a grant from Abbott BV and Health~Holland.

- Mol reports receiving grant funding from Abbott Laboratories and Health~Holland during the conduct of the study.

- Van Royen reports receiving grant funding and personal fees from Abbott Laboratories during the conduct of the study; grants from Koninklijkie Philips NV, Biotronik, and Medtronic; and personal fees from MicroPort, Bayer AG, and RainMed Medical outside the submitted work.

Comments